A Conversation on Art & Science: Emily S. Damstra & Stephen Heard

This year, UNB Biology Professor Stephen Heard published Charles Darwin’s Barnacle and David Bowie’s Spider. To bring the organisms in his book to life, he worked with illustrator Emily S. Damstra of Guelph, Ontario. We shared a virtual exhibition of these illustrations and their accompanying excerpts here. As a complement to the show, the artist and writer gave their thoughts on cross-disciplinary collaboration and the intersections of science and art. Read on.

What is your book about and how did Emily’s illustrations enhance that narrative?

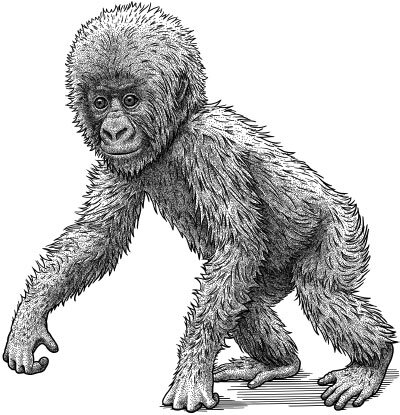

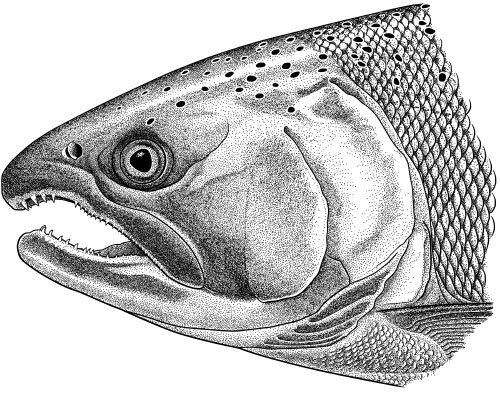

Stephen: My book is about scientific names of plants and animals – in particular, about scientific names that honour, or recognize, people. Like David Bowie’s spider (Heteropoda davidbowie)! Except it really isn’t about the names. It’s really about how those names serve as a window on the personalities of scientists and the culture of how we do science. I really wanted the book to have illustrations, because it tells a lot of stories, and each story has (at least) three characters: a plant or animal species that bears somebody’s name; the person whose name it bears; and the person who gave it that name. I think it’s easy enough for a reader to picture, and relate to, one of the people. It’s not so easy for a reader to picture the plant or animal character, but an illustration brings that character to life. I love Emily’s style because it does bring creatures to life. Her work is scientifically accurate, but at the same time she manages to make her illustrations show life, and even personality, in a lemur or a lizard or a snail.

Emily: There is a long history of black and white line and/or stipple drawings accompanying scientific texts because artists can achieve great clarity with this type of illustration, and publishers can reproduce it reliably and inexpensively. Even though Steve’s book is for a general rather than strictly scientific audience, the stories he tells about species names and scientists are rooted in original descriptions in the scientific literature. Black and white stipple drawings evoke this scientific association. Although my illustrations are in a seemingly traditional medium, I created them digitally and favoured lively poses over scientific angles, so I think this body of work has a contemporary vibe, akin to Steve’s writing.

Our technology today allows us to collaborate across great distances. Tell us about your process of working together.

Emily: It’s wonderful to be able to work out of a small room in my home while collaborating with people from around the world. For this project, Steve would email chapter drafts to me so that I could absorb the complete narrative surrounding a particular species I was to illustrate. I savoured these opportunities to read the stories Steve tells so skillfully; his book is the sort I would read even if I had no involvement in it. Some chapters mention many species, and for these—to my delight—Steve would sometimes seek my opinion about which to illustrate. Additionally, he was also open to my ideas on how to depict each species; he gave me quite a bit of creative freedom, and his enthusiasm was evident throughout the process. Steve is the best kind of client!

Stephen: Well, it wasn’t as high-tech as you might imagine. Mostly, I would email Emily a suggestion for a species I’d like illustrated – sometimes with a photograph, but sometimes just the species name. We’d exchange a few emails about what the illustration might look like, and then Emily would send me a digital draft. Opening the file with a new draft would make my day, every single time! Often I’d just love the draft as it was; sometimes I’d make a few suggestions – either in words or in scribbles on a copy I’d printed out (I still like to see drafts on paper). Emily would tinker, and soon we’d both be happy with her draft – then she produced a finished detailed version. We hadn’t met in person when we collaborated on the book. I still haven’t seen Emily’s studio, but I’d love to watch her process of creating.

In what ways do you use art within your scientific practice? Science within your artistic practice?

Emily: As a natural science illustrator who aims to create accurate and detailed images, science plays a significant role in my work. I regularly seek advice from scientists and read scientific texts in order to understand the subjects I illustrate. In fact, I first “met” Steve in 2015 when I emailed him with some questions about goldenrod, a subject I was illustrating at the time. In my research, I learned that he had studied this subject and I hoped he might be able to help me make sense of a complex topic. He was incredibly generous with his time and expertise.

Stephen: If you’d asked me a few years ago about using art within my scientific practice, I’d have said that I didn’t. But I now realize that I do: in the sense of the literary arts. Scientific writing is not literary in the conventional sense, but we use structures and devices in common with literature writing – for example, using sentence structure and rhythm to directs emphasis. I’ve become more aware of this since beginning to write non-technical works and especially work for the general public, like Charles Darwin’s Barnacle. As a result, I’m now deliberate in attempting touches of style in my scientific writing that make it pleasing, or effective, or – ideally – both.

Are science and art distinct and separate entities?

Emily: It’s hard to answer this because “science” and “art” refer to such broad entities, with a huge diversity of practitioners. If I narrow this down to biologists and natural science illustrators I do think there is a good deal of overlap, especially in terms of observational skills. However, I think the differences are still greater than the similarities.

Stephen: They’re definitely different, but that doesn’t mean they’re always separate. Science and art both involve looking at the world and then saying things about how we understand it. But they’re (mostly) different ways of looking, and they involve (mostly) different ways of saying things about what we’ve seen. The differences are more obvious than the points of overlap, so it’s more fun to talk about the latter. Artists are often very good observers, and a number of species have been described from etchings and paintings rather than from physical specimens – for example, in the work of the 17th-century artist and entomologist Maria Sibylla Merian. I’m interested in the overlap on the “saying” side too, as scientific writing bleeds into art and art into scientific writing. I have a colleague, Madhur Anand, who writes poetry – some of which uses “found” lines from her scientific papers. And Vladimir Nabokov, the novelist, was also a taxonomist who worked with butterflies. The butterflies crop up in a couple of his novels – and the novelist crops up in a couple of his scientific papers, in the form of occasional sparkling metaphors and turns of phrase.

Describe your particular way of observing the world around you. How has it been impacted by your choice of career?

Stephen: Gosh, I don’t know what my way of observing the world is! I do know that I tend to look down (because I watch for insects and plants) while my birder friends look up. But I don’t think that’s what you mean. I would say that I tend to look for pattern and to see individual animals, or plants, or rocks as examples of interesting general processes. So I tend to see competition in a dense forest, or natural selection in a gull’s midden of cracked shells. I do think that’s a result of my career as a scientist, trying to figure out some of those processes that shape our world. But I also think compared to some of my colleagues, I see more underlying process and less natural history of the individual, which is not always good!

Emily: Like Steve said, I’m not exactly sure how I observe the world! One thing I’ve noticed in recent years is that I’ve become much more aware of how nature is depicted in our culture, and I attribute this awareness to my practice as a natural science illustrator. When I see plants and animals depicted in illustrations and animations everywhere in our world—from emojis to popular movies to billboard advertisements— I can often tell whether or not their creator was a good observer of the subject. As to whether or not I have been known to make remarks about inaccuracies, you will have to ask my husband. ;)

Does specialization limit or expand the way we see and understand our surroundings?

Stephen: Both, of course. Our world is complicated enough, and our understanding of it is deep and rich enough, that you need to specialize if you want to engage seriously with what is known about something. That’s why we listen to virologists and public-health experts about Covid-19, for example (the fact that not everyone understand this is tragic – literally tragic, as it is killing people). At the same time, though, specialization can limit your view, and so there are insights to be had from considering one field from the perspective of another. The trick is balancing these, and at least in science, I think usually the outside perspective needs to be the teaspoon of salt, not the five cups of flour (maybe you can tell I’ve been baking bread).

Emily: This is a great question, and I think Steve articulated my own thoughts quite well.

What advice would you give to others who may be interested in a cross-discipline collaboration?

Stephen: First, do it! Second, have the attitude that you’re going to watch for and learn about differences between disciplines. Those may be differences in the way we think about observation, or how we express ourselves, or they could be more process-related, like differences in how people work in collaboration or even in business practices. If you assume everyone works the way you do, there’s the potential for conflict, and you also sacrifice the opportunity to learn. But in a good collaboration the moments of confusion or friction are minor and far outweighed by the joy.

Emily: Also, one cannot always imagine where such a collaboration might lead and how one might grow from a cross-disciplinary experience, so it’s well worth a try.

If you enjoyed the interview above, click here to immerse yourself in scientific naming and illustration with Emily & Stephen’s virtual exhibition Charles Darwin’s Barnacle.

If you loved the illustrations above, see Emily S. Damstra’s wonderful portfolio by visiting her website here.

If you can’t get enough of Stephen Heard’s humorously insightful writing style, find his book Charles Darwin’s Barnacle and David Bowie’s Spider here and his blog, Scientist Sees Squirrel, here.

For more exciting stories on the intersection of nature and art, get CreatedHere’s Issue 12: Enviro here.